THE AFRICAN COURT ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS AND THE POSSIBLE ROLE OF THE PAN AFRICAN PARLIAMENT IN PROMOTING THE COURT

PRESENTATION BY

THE HONORABLE JUSTICE GERARD NIYUNGEKO,

PRESIDENT OF THE AFRICAN COURT ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS

DURING THE 5TH ORDINARY SESSION OF THE SECOND PARLIAMENT OF THE PAN AFRICAN PARLIAMENT

6OCTOBER 2011

MIDRAND, SOUTH AFRICA

- INTRODUCTORY OVERVIEW OF THE AFRICAN COURT ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS.

- Introduction

While this presentation’s aim is to try and distil the areas in which the Pan African Parliament (PAP) can help in the promotion of the Court, it is necessary to start by giving a general background on the Court. While the relationship between the Court and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights is easily discernible from the Protocol establishing the Court, such is not the case with PAP. And without clear understanding of the mandate of the Court, the manner in which it came into existence as well as its organizational function, it may not be clear what role PAP can play in the promotion of the Court.

- Establishment

As you may be aware, the Court was established pursuant to Article 1 of the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Establishment of an African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (the Protocol).

In 1998, the 34th Ordinary Session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the Organization of African Unity (now the African Union), meeting in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, adopted the Protocol. This Protocol entered into force on 25 January 2004, paving the way for the operationalization of the Court.

In January 2006, the first eleven (11) Judges of the Court were elected and in July of the same year, they were sworn in before the 7th Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the African Union. In 2006, the Court began operations.

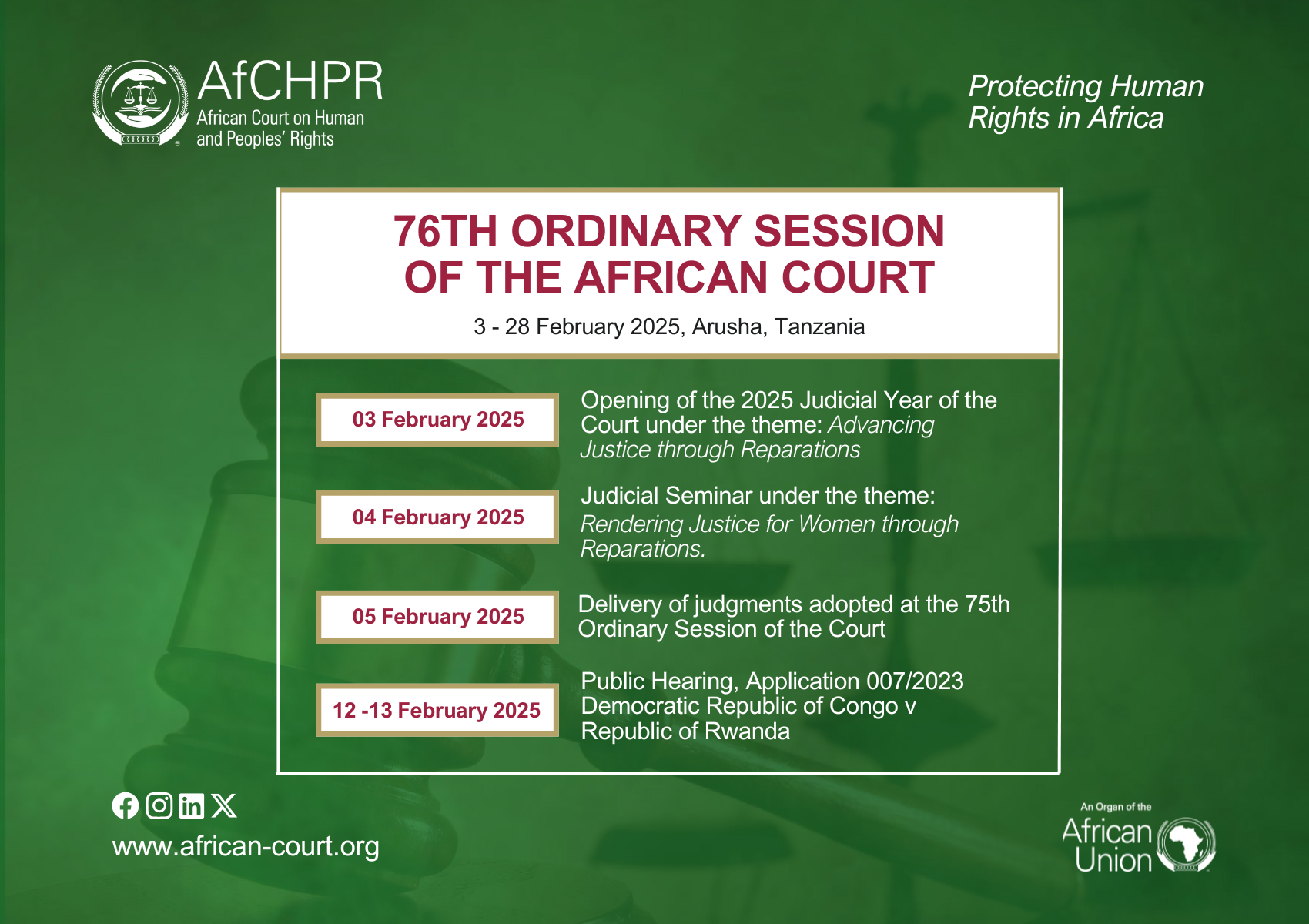

The Court has its seat at the Julius Nyerere Conservation Centre, Tanzania National Parks (TANAPA) complex, Dodoma Road, Arusha, Tanzania, where it relocated from Addis Ababa in August 2007.

- Composition

The Court is composed of eleven Judges, elected in their individual capacities from among eminent African jurists and judges of proven integrity, qualifications and experience; having been nominated by individual Member States. The election is also based on equitable representation of gender, the five major African regions, and major legal systems and jurisdictions. No two Judges can be from one Member State.

Judges are nominated by States Parties to the Protocol and elected by the Assembly of Heads of States and Government of the African Union, for a period of six years, renewable only once.

The current composition of the Court is as follows: Hon. Justice Gerard Niyungeko, President (Burundi), Hon. Sophia A.B. Akuffo, Vice President (Ghana), Hon. Jean Mutsinzi (Rwanda), Hon. Bernard M. Ngoepe (South Africa), Hon. Modibo T. Guindo (Mali), Hon. Fatsah Ouguergouz (Algeria), Hon. Joseph N. M. Mulenga (Uganda), Hon. Augustino S. L. Ramadhani (Tanzania), Hon. Duncan Tambala (Malawi), Hon. Elsie N. Thompson (Nigeria), and Hon. Sylvain Ore (Cote d’Ivoire), Judges.

- Mandate

The mandate of the Court is to complement the African Commission on Human and Peoples Rights in the protection of human rights in Africa. The Court can therefore only handle cases of human rights violations. In their wisdom, African leaders decided that it was necessary to establish a Court that would hand down binding and enforceable decisions on human rights violations, in contrast to the Commission which can only make non-binding recommendations.

- Role of the Court in contentious matters

- Jurisdiction of the Court

In accordance with Article 3 of the Protocol, the Court has jurisdiction over all cases and disputes brought to it relating to the interpretation and application of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (hereinafter referred to as ‘the Charter’), the Protocol and any other relevant human rights instruments ratified by the State concerned.

- Access to the Court

The following entities can submit cases to the Court: The African Commission on Human and Peoples ‘Rights; States parties to the Protocol; African Intergovernmental Organizations; Individuals and Non-Governmental Organizations (provided that the States against which they act has made a special declaration accepting the competence of the Court to hear cases brought by individuals and NGOs)

- Admissibility of applications

To be admissible, an application has to fulfill a certain number of conditions, the most important being that it should be filed after exhausting local remedies, if any, unless it is obvious that this procedure is unduly prolonged.

- Possibility of amicable Settlements

The Court also has power to promote amicable settlement of cases pending before it in accordance with the provisions of the Charter.

- Findings

When the Court finds that there has been a violation of human or peoples’ rights, it will issue appropriate orders to remedy the violation, including the payment of fair compensation or reparation.

In cases of extreme gravity and urgency, and when necessary to avoid irreparable harm to persons, the Court can adopt provisional measures as necessary. An example of a situation which calls for adoption of provisional measures is when a death sentence is to be executed and the appeals process has not been exhausted.

- Judgment

The Court gives its judgment within ninety (90) days of having completed its deliberations. Its judgment is final and not subject to appeal.

However, in light of new evidence, which was not within the knowledge of a party at the time the judgment was delivered, a party may apply for review of the judgment. This application must be within six months after that party acquired knowledge of the evidence discovered.

The Court also has power to interpret its own decisions

- Enforcement/execution of the Court’s judgments

The Court’s Protocol obliges States Parties to undertake to comply with the judgment in any case to which they are parties within the time stipulated by the Court and to guarantee its execution.

It also provides that in its report to the Assembly of Heads of States, the Court shall specify in particular, the cases in which a State has not complied with the Court’s judgment.

Finally, it provides that the Executive Council of the African Union shall monitor the execution of the judgment on behalf of the Assembly.

- Role of the Court in advisory matters

The Court may, at the request of a Member State of the African Union, any of the organs of the African Union, or any African organization recognized by the African Union, provide an opinion on any legal matter relating to the Charter or any other relevant human rights instruments, provided that the subject matter of the opinion is not related to a matter being examined by the Commission.

- Main achievements of the Court

From 2006 to 2008, the Court worked mainly on making itself operational from the administrative perspective: budget, structure of the Registry, recruitment of staff; seat of the Court; Rules of procedure, etc.

Starting from the end of 2008, the Court was ready to receive its first cases. But, partly because the Court was not well known, from 2008 to 2010, the Court received and dealt with only one case.

But, since the beginning of 2011, the Court has started receiving an increasing number of cases. Up to now, the Court has indeed received twelve cases in contentious matters and one request for advisory opinion. One can say that the Court has become operational from the judicial perspective as well.

- Main challenges faced by the Court

Among the main challenges the Court is facing are the following : low rate of ratification of the Protocol establishing the Court; the very limited access to the Court by individuals and non-governmental organizations; the lack of awareness about the Court by Africans .

It is mainly against these challenges that the Pan African Parliament can play an important role in promoting the Court.

- THE ROLE OF PAP IN PROMOTING THE COURT

The support of PAP in the promotion of the Court is therefore crucial to enable it to discharge its mandate, both in terms of its administrative, institutional and operational frameworks.

- Ratification of the Protocol

Every Member State of the African Union is a State Party to the Charter. In contrast, since the adoption of the Protocol in 1998, only [twenty six (26)] of the fifty-three (53) Member States of the African Union have ratified it. As at March 2011, these States are : Algeria, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cote d’Ivoire, Comoros, Congo, Gabon, the Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Libya, Lesotho, Mali, Malawi, Mozambique, Mauritania, Mauritius, Nigeria, Niger, Rwanda, South Africa, Senegal, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia and Uganda.

In its function of providing oversight, advisory and consultative services, PAP is in the unique position of being able to influence the rate of ratification of the Court’s Protocol. Through its committees on Justice and Human Rights, and Cooperation, International Relations and Conflict Resolution, PAP appears to have the necessary muscle in this regard and the Court is particularly interested to see parliament assisting the Court to ensure that Member States take seriously the treaties and conventions they have adopted and make concrete advances to implement them.

- Deposit of the Declaration allowing individuals and NGOs to access the Court

Even more seriously than the status of ratification of the Court’s Protocol, is the rate of deposit by member states of the declaration required by Article 34(6) to permit individuals and NGOs to access the court directly. As at March 2011, only [five (5)] of the 26 ratifying countries have made the Declaration allowing NGOs and individuals direct access to the Court. These are Burkina Faso, Ghana, Malawi, Mali and Tanzania.

That the Court’s effectiveness is seriously affected by this state of affairs cannot be overemphasised. As of to date, only three cases from Tanzania and Malawi have come to the Court, that are not constrained by this provision. Yet serious human rights violations occur across Africa every day, for which there is no recourse to the Court. It cannot possibly have been the intention of African Union member states to create a Court to provide human rights protection, provide it with funding and then close the door against the very purpose for which it was created. The Court therefore believes that PAP has a role to play to ensure the effectiveness of the Court, particularly since all members here represent parliaments that annually vote for contributions in national budgets to support the Court.

- Raising awareness about the Court

PAP can contribute to raising awareness on the African Court among other Members of National Parliaments, and among the public at national level in general.

Through its own programs and activities, PAP and its Committee on Justice and Human Rights can also contribute to the same. In this regard, the Court welcomes any invitation to be part of the Committee’s activities aimed at promoting human rights in general and the Court itself in particular. On its part, the Court will go on involving members of the Committee in all its relevant activities, and is available to jointly organize with the Committee, promotional activities that they will have agreed to undertake.

- Request for advisory opinions

In making recommendations relating to matters pertaining to human rights, democracy, good governance and the rule of law as well as those recommendations aimed at contributing to the attainment of the objectives of the African Union in accordance with Article 11 of its Protocol, PAP could conceivably utilize the advisory opinion of the Court. Article 4 of the Court’s Protocol entitles any organ of the African Union to seek the advisory opinion of the Court. Further, PAP, through its membership could encourage Member States to seek the advisory opinion of the Court when considering any legislation that could have an impact on human and peoples’ rights.

- Facilitating National Human Rights Enabling Legislation

The primary responsibility for the protection of human rights lies with national jurisdictions. The Court is only there to provide subsidiary protection, and even then, its decisions must still be effected by and within national jurisdictions. The Court has already recognized the symbiotic relationship between itself and national jurisdictions, even though it is not an appellate Court for them. For that purpose, a relationship through a series of colloquia is already being built to strengthen cooperation and complementarity. PAP, representing as it does, national parliaments, is an integral part of that relationship, as it is only through national legislation which enables human rights protection that continental Africa, through the Court, can effectively protect human rights. PAP can therefore develop and establish policies and guidelines that can assist national parliaments in this regard in line with its harmonizing or coordinating the laws of Member States in accordance with Article 11(3) of its Protocol.

3. CONCLUSION

The low rate of ratification of the Protocol and the even lower rate of Declarations, when contrasted with the continuously deteriorating human rights situation on the continent raises a question of whether African leaders are truly committed to ensuring the Court’s functional effectiveness and development. The resultant slow rate of submission of cases to the Court is an impediment to the development of a culture of respect for human and peoples’ rights. The African Union and its organs, including PAP, are duty bound, in pursuit of a justice, democracy and the rule of law, to actively participate in the promotion of the Court to ensure its effectiveness. For its part, the Court pledges to discharge its role as the judicial pillar of the African Union with independence, justice and fairness.